When pruning fruit trees, you’ll find lots of different information about how exactly to prune them correctly. Fruit trees have been grown by humans for thousands of years in all parts of the world, which has created a lot of information to digest! Thankfully, there are some tried and tested techniques for the types of fruit trees that can grow in Utah.

The Importance of Pruning Fruit Trees

Pruning fruit trees is essential to healthy growth and optimal fruit production. Pruning, or selectively removing branches, buds, and/or roots improves a tree’s health, growth, shape, size and fruit production.

When branches grow too close to one another and cross or rub against each other, fruit production will be hindered and in some cases, the health of the tree may be compromised. By thinning and removing branches, you allow room for light and airflow to reach the fruiting wood, resulting in better fruit production.

Pruning also makes harvesting fruit easier and more manageable, especially in the backyard orchard. Modern fruit trees have been bred to produce large fruits, so pruning is often necessary to prevent limb breakage, control harvest volumes to practical levels, and position the fruit in the tree to make it easier to pick.

When should you prune fruit trees?

First, let’s talk about when you want to prune fruit trees.

The ideal time to prune a fruit tree is in the period from late Winter into early Spring, when the tree is dormant. Dormancy is the period of time during the winter when a tree is alive and conserving energy but not actively growing. Pruning cuts are less stressful and damaging on a tree during this period. For this reason, later Winter is also a good time to plant new fruit trees.

Pruning during a tree’s dormant period is better for us too because it’s easier to see what you’re doing when a tree is out of leaf. This is the time for major pruning projects to shape a tree, contain its growth, and invigorate growing buds and spurs by removing excess growth. Pruning during the growing season might be necessary for overly vigorous trees but should be done with caution and only after the fruit has been harvested.

The Basics of Pruning Fruit Trees – What to Prune

Pruning fruit trees ought to be considered in two phases: a first phase when the tree is young where its essential shape is determined and reinforced; and a second phase when the tree is at least 5 years old where fruiting wood is maintained and renewed through thinning and tipping.

General Pruning Guidelines

Pruning yearly is recommended to promote vigorous growth and better fruit production. In both phases, general pruning principles apply, including removing the following:

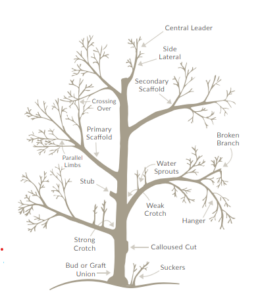

- Dead, hanging or damaged branches – These either contribute nothing to a tree’s health and fruit production or can be vectors for fungus, bacteria or pests to further compromise the tree’s health.

- Diseased branches – Branches with obvious disease or pest infestations should be removed. If there is a large or concerning problem, you may need to treat the entire tree before it blooms.

- Water Sprouts and Suckers – Undesirable growth on a tree or rootstock that will suck resources away from fruit production. These should be pruned off.

- Crossing or rubbing branches – Branches that are too close to each other will crowd out future fruit production. Branches that rub against each other can cause damage and allow pathogens to enter.

For Young Trees – Shape Pruning

The first phase – shape pruning – can begin as soon as the tree is planted, though some orchardists choose to delay pruning until a tree’s second season to provide for better root establishment. Either way, this first phase is designed to create a primary scaffold to support the eventual weight of a fruit harvest.

There are three main types of pruning strategies, which will be discussed in more detail below.

For Mature Trees – Maintenance and Renewal

The second pruning phase – maintenance and renewal – begins after the trees have matured to a point where full harvests are more likely to occur, usually 5 years after they’re planted. By now, the tree’s essential structure has been determined, so what’s necessary isn’t grand shape pruning. Instead, thinning is employed to remove branches, promoting space for airflow, light penetration, and, by extension, proper fruit maturation. Heading cuts are also used to remove portions of branches so as to direct their growth away from each other and the tree’s interior, stimulate bud or spur development, and maintain the overall tree appearance.

You’ll find that heavy pruning might encourage the formation of non-fruiting, vertical branches called water sprouts and other vegetative growth that will require removal because they sap energy away from fruiting wood. Light pruning, on the other hand, might encourage too heavy fruit set, resulting in smaller, poor quality fruit and possible branch breakage. Consequently, orchardists need to strike a balance between heavy pruning and renewing fruiting wood.

How should you prune fruit trees?

When making cuts while pruning fruit trees, there are a few things to consider.

Types of Pruning Cuts

- Heading Cuts – Shortening a branch or shoot to encourage lateral growth

- Thinning Cuts – Removing an entire branch or shoot back to a lateral branch

- Stay Sharp: Always start with sharp and disinfected pruners, for smaller branches, or loppers if you’re taking out larger branches.

2. Examine the Angle: When looking at branches to remove, first examine the “Crotch Angle” where the branch meets the trunk. Aim to keep branches that have wider, strong crotch angles, and remove branches that have narrower weak crotch angles.

Strong Crotch Angle: 45-60 degrees from trunk

Weak Crotch Angle: More than 60 degrees from trunk

3. Avoid Tearing: Cut away most of the branch before cutting near the trunk. That way you can make a clean cut without the weight of the branch tearing from the trunk and causing an unnecessary wound.

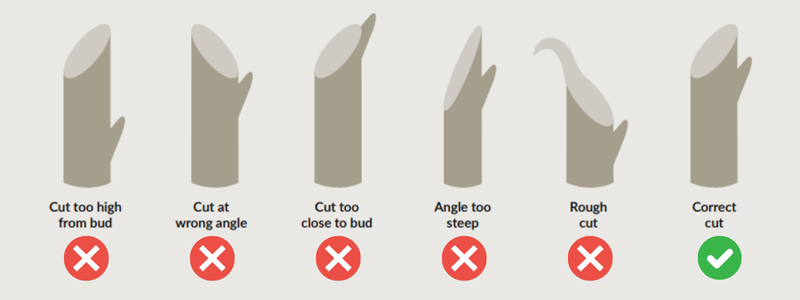

4. For Heading Cuts: For cutting a branch back some but not removing it entirely, aim for an angled cut just above a new bud formation. This applies when pruning most flowering trees and shrubs, not just fruit trees.

Can you prune fruit trees to keep them small?

With the right pruning techniques, any tree can be kept small enough to accommodate small spaces and practical harvests. Given that most fruit trees available in the marketplace have been grafted onto semi-dwarfing rootstock, these trees will already max out at about 60-75% standard size. Planting genetic dwarf fruits may also help with space concerns.

Basics of Pruning Fruit Trees – Shape Pruning Strategies

When it comes to pruning fruit trees to create a manageable shape and size, there are a few different options to work with. Different types of fruit trees do better with certain types of training based on how their branches grow. The most common of these training or shaping methods are Central/Modified Leader, Open Center/Vase, and Espalier.

Central Leader / Modified Central Leader Training for Fruit Trees

A central leader shape functions like a pyramid or Christmas tree, with a single main trunk and well-balanced lateral branches. This type of pruning works well for fruit trees whose branches have an upright growth habit, as opposed to a spreading habit.

Ideal for:

Apples

Pears (European and Asian)

European Plums (Prune Plums)

Sweet Cherries

Persimmons

Walnuts

Jujubes

How to prune a Central Leader tree

To establish initial shape:

- Identify the main/central leader.

- Designate “tiers” of branches (“scaffolds”) that are spaced evenly around the trunk; Tiers should be about 18”-24” apart.

- Branches should be angled 45-60 degrees from the leader.

- Prune away some of the branches off of the scaffolding branches to achieve openness between the branches.

To maintain shape and produce fruit:

- Fruit is produced on “spurs” (short, stubby branches) that are 2 or more years old and branch off of the scaffolding branches.

- Prune new, vegetative branches that grow off of the scaffolding branches or trunk to allow light to get to the spurs.

Central Leader vs. Modified Central Leader: A Central Leader shape allows the leader to grow uninhibited, resulting in a taller tree and maximum fruit production. A Modified Central Leader shape is achieved when the leader is tied or pruned in a way to allow for a smaller tree and a more rounded crown.

For Modified Central Leader (Smaller Tree):

Follow steps 1-4, then cut off main/central leader above highest desired lateral branch

Open Center / Vase Training for Fruit Trees

An Open Center / Vase functions like an upside-down pyramid, with main branches coming off of the main leader (which is removed just above) nearer to the base of the tree. This type of pruning works well for fruit trees whose branches have a more horizontal spreading growth habit, as opposed to an upright habit.

Ideal for:

Apricots

Nectarines

Peaches

Japanese/Asian Plums

Interspecific (Pluot, Nectaplum, Aprium)

Sour/Tart Cherries

Almonds

Figs

How to prune an Open Center / Vase tree

To establish initial shape:

- Cut the main/central leader at a point between 2’ and 3’ from the ground.

- Choose 3-4 primary branches (“scaffolds”) to leave for growth.

- Scaffold branch angels should be angled 45-60 degrees from the trunk

To maintain shape:

- Prune to completely remove branches that are growing inward toward the center of the tree.

- Prune/thin dead, diseased, damaged or crossing branches.

- Prune 40-50% of previous year’s growth to stimulate new growth.

- Fruiting buds are formed on 1-year-old wood (branches formed in the previous year)

- Choose pencil-sized old wood to leave for fruit production. Trim down to 6”-8” long.

Espaliered Fruit Trees

Espalier is a process by which a woody plant is trained in a two-dimensional style usually against a wall or fence line. Espaliered fruit trees require dedicated pruning and training to grow horizontally and within narrow boundaries.

Fruit trees are espaliered for growing in smaller spaces, but also for aesthetic purposes. You will typically only see apples and pears already pruned for purchase in nurseries because they require less extensive yearly renewal pruning, though you can turn just about any kind of fruit tree into an espalier if you’re willing to train and prune it yourself.

Pollination Tip – Many espalier trees have grafted branches of different varieties of fruit, such as 4 or even 6 different kinds of apples. This helps with pollination, as you only need one of these trees instead of a pair of two trees.

Spurs – Where Trees Produce Fruit

When pruning fruit trees, it’s important to know the parts of the tree where fruit grows, so that you don’t accidentally prune off your harvest for the year.

What are Spurs?

Most fruit trees form short, knobby shoots called spurs from which flowers develop and, if pollinated, a cluster of fruits will form. Spurs grow off of branches but are distinct forms of growth from other parts of the tree, such as the trunk and branches. These spurs are different from branches because of their compressed growth structure that keeps them less than 4 inches in length and often no more than an inch or two long.

Spurs are different from thorns (though they might be similar in size) because instead of being smooth and sharp, they’re blunt and wrinkled, with a rosette of leaves behind a fairly large bud at the tip. Fruit spurs grow very slowly and most require at least two years to become productive and can host fruit anywhere from 3 to 12 years after that.

Spurs behave differently depending on the fruit tree species in question.

Long-producing spurs – Apples, Pears and Sweet Cherries

These trees form fruit on spurs that are 2 years old and older. These spurs only grow at most an inch a year but can host fruit for up to a decade or more. This means these varieties require only moderate pruning once they are trained and reach bearing age to stay productive.

2-5 Year Spurs – Apricots, Plums, Interspecific

Apricots also bear fruit off of spurs at least 2 years old but these spurs are active for no more than 3 years after that. This means these trees require pruning with the aim of renewing growth and spur production more often. The same is true for both European plums (the ones typically used for drying into prunes) and Japanese plums (more typically found in stores for fresh eating), though plum spurs can remain productive for 5 years or more.

1 Year (Lateral Twigs) – Peaches and Nectarines

And then there are peaches and nectarines, which have identical fruiting habits but are very different from other fruit trees. Instead of fruiting from spurs, they produce from lateral buds formed on only year old twigs, meaning these trees require new fruiting wood every year and must be continually stimulated to grow new wood to stay productive. Probably no other fruit tree responds more to proper pruning and declines if neglected than a peach or a nectarine, so backyard orchardists need to prune these trees more heavily and more often than other varieties.

A Note about Fruit Tree Sizing

Fruit Tree growers use a process called grafting to grow identical clones of plants onto what’s called a rootstock, as opposed to growing plants from seed. This ensures that the fruit you will get will be the exact same genetically and not a genetic variation.

Grafting is also used to influence the growing characteristics of these varieties. For instance, most of the fruit trees available in nurseries are labeled as semi-dwarf. This means that when these trees were grafted, growers chose rootstock that limits the vigor of the tree to keep it smaller than it would grow otherwise.

Examples of how grafting affects the size of trees include:

- Standard size trees: These trees are grafted only to produce clones and not to moderate their eventual size, meaning the only way to affect these trees’ dimensions is through pruning. This is important because the standard size for many fruit trees is surprising. Standard cherry trees can grow to more than 30 feet tall, as can apples and pears, which makes practical harvesting difficult. Given this, it is rare to find standard size fruit trees available in the marketplace.

- Semi-dwarf trees: These trees are created by grafting scions onto rootstock that limits the vigor of the tree, thereby keeping tree size to roughly 60-75% of standard dimensions. Most popular varieties you’ll find in the nursery are semi-dwarf trees.

- Genetic dwarf trees: These trees are not dwarfed because of their rootstock. Instead these particular varieties are selected because of their dwarfing genetics. Genetic dwarf trees grow very slowly, usually getting no more than 10 feet tall, making them highly sought after for space limited gardens. However, given the size is a factor of the variety and not the rootstock, most popular fruit varieties are not available in a genetically dwarfed form.

Buying bigger isn’t always better

When consumers shop for trees in general, most are looking for the biggest tree available for a given price, considering the time it takes for trees to reach a decent size relative to a person’s lifetime. Purchasing fruit trees is a little different, however, because of the kind of initial pruning often necessary to establish a tree’s basic shape. Smaller, younger trees have less heavy branching, making it easier to remove them without undue stress to the tree, and this branching is typically lower down on the trunk, which helps to accommodate the unique vase shape so common in both production and backyard orchards.

Fruit Tree Pruning Terms:

Branch Collar

Chill Hours – The minimum period of cold weather after which a fruit-bearing tree will blossom.

Dormancy – The period in which a tree is

Drupe (Stone Fruit) – A type of fruit in which an outer fleshy part surrounds a single shell, known as a pit or stone, with a seed (kernel) inside. Typical stone fruits grown in Utah include peaches, nectarines, cherries, plums, apricots, almonds, and interspecific varieties like pluots and apriums (plum/apricot hybrids). More exotic fruits such as jujubes, coffee beans, mangoes, olives, dates, cashews and pistachios are also drupes.

Espalier

Graft

Pome – The fruit produced by some plants in the Rose family. Pomes have an internal fibrous core containing multiple seeds, all covered in an outer, thicker fleshy layer. Edible fruits such as apples, crabapples, pears, quince, serviceberry, hawthorns, and aronia (chokeberry) are pomes. Additionally, the fruits of pyracantha, cotoneaster, rowan (mountain ash), photinia and Indian hawthorn.

Rootstock

Scion

Semi-dwarf

Spur

Thinning